Tailings Recycling: A Complete Guide to Sustainable Mining

3503Unlock the economic and environmental benefits of tailings recycling. Discover how this sustainable solution transforms mining waste into valuable materials.

View detailsSearch the whole station Crushing Equipment

Heap leaching is often mischaracterized as a simple mining method. While the capital expenditure is lower than a flotation plant, the operational complexity is significant. A heap is not merely a pile of rocks treated with chemicals; it functions as a massive, living bio-chemical reactor. Projects frequently fail due to geotechnical engineering flaws—such as clogging, channeling, and compaction—rather than purely chemical issues. Successful operation requires a system design that strictly balances hydraulics and kinetics to prevent the ore pile from becoming impermeable.

Determining recovery rates based solely on bottle roll tests is insufficient for industrial applications. While bottle rolls provide the theoretical maximum dissolution, they fail to simulate the critical physical factors of a real heap, such as the weight, pressure, and compaction of a 6-meter lift. To accurately determine Heap Leaching Process Design parameters, reliance on Column Leach Tests is essential. Mineralogy dictates process success. For example, if gold is encapsulated in sulfides, simple cyanide leaching will fail without pre-oxidation or bio-leaching.

In 2026, the industry focus is heavily on the “Scale-Up Factor.” A lab column might recover 90% of the soluble metal, but field efficiency often drops due to channeling and segregation. Running columns at the exact bulk density expected in the actual heap is recommended. This practice reveals the critical “load-permeability” relationship. If the column collapses or seals off under pressure in the lab, the heap will almost certainly fail in the field. Critical data points such as porosity under load, acid/cyanide consumption, and leaching kinetics must be analyzed before equipment procurement to avoid costly errors like those seen in projects where heaps compacted into impermeable blocks.

“Comparing heap leaching with other methods? Reference the Agitated Tank Leaching solutions for high-grade alternatives.”

Selecting the Ore Crushing Size involves a strategic trade-off: finer crushing increases recovery speed by exposing more mineral surface, but coarse crushing maintains the permeability needed for liquid flow. Finding the equilibrium point is the most critical decision in the process. For most gold ores, this optimal range typically falls between 12mm and 25mm. Crushing too fine (below 5mm) generates excessive fines that block liquid flow, creating dry zones where no leaching occurs. Conversely, crushing too coarse (above 50mm) prevents the lixiviant from penetrating the rock matrix to reach the target mineral.

To achieve this balance, a multi-stage crushing circuit is standard. This typically involves a Jaw Crusher for primary reduction followed by a Cone Crusher for final sizing. The objective is to produce a uniform particle distribution rather than just small rocks, ensuring both rapid kinetics and sustained hydraulic flow throughout the heap’s life.

| Crushing Stage | Equipment Type | Target Output | Impact on Heap Dynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Jaw Crusher | 100mm – 150mm | Reduces Run-of-Mine (ROM) to manageable size. |

| Secondary | Cone Crusher | 25mm – 40mm | Creates micro-fractures for solution entry. |

| Tertiary | VSI / HPGR | 6mm – 12mm | Maximizes surface area but increases risk of fines. |

Fines migration is the primary cause of failure in heap leach pads. Ores containing high clay content or generating more than 10% fines (-100 mesh) during crushing require Mineral Powder Briquetting Machine technology or drum agglomerators. This process utilizes a binding agent, such as cement or lime, to attach fine particles onto coarser rocks. This creates stable pellets that prevent fines from washing down and clogging the void spaces within the heap.

The critical factor in successful agglomeration is the curing time. A common operational error is skipping the curing phase. Agglomerated pellets must be allowed to “cure” (harden) for 24-48 hours in a stockpile before being stacked on the pad. Stacking wet, soft pellets immediately leads to disintegration under the massive weight of the heap layers. Once the pellets break down, fines are released, leading to a clogged, impermeable pad and a cessation of recovery. Binder dosage typically ranges from 2-5 kg of cement per ton of ore, and moisture levels must be carefully controlled to ensure pellets are damp but not saturated.

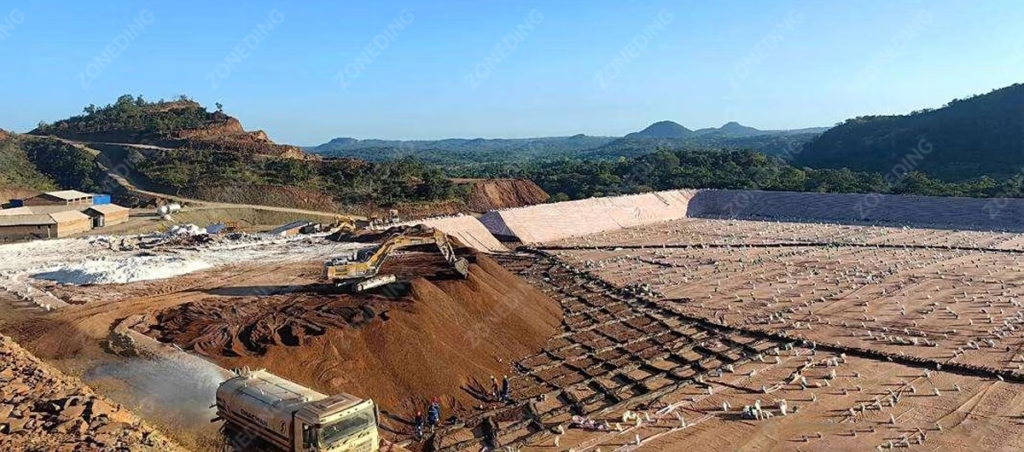

To maintain porosity, driving trucks or dozers directly on top of the leach pad must be avoided. Heavy tires cause severe compaction, crushing the ore pores and creating “dead zones” where solution cannot flow. The industry standard for high-performance heaps is “Retreat Stacking” using Mobile Crushing Station conveyors or grasshopper stackers. This method ensures that the heavy equipment always moves away from the pile, leaving the fresh ore loose and uncompacted.

Beyond the stacking method, the design of the liner system is crucial. While the plastic liner (HDPE) prevents chemical leaks, the Overliner—a 500mm layer of material placed directly on top of the plastic—acts as the hydraulic safety valve. Run-of-Mine ore is unsuitable for this layer. Instead, crushed, screened, and washed gravel (100% passing 1 inch) is required. If the overliner clogs with fines, fluid pressure (phreatic head) builds up inside the pile, which can destabilize the slope and cause catastrophic landslides.

The selection of the Lixiviant Distribution System is dictated by the specific climate and the oxygen requirements of the ore. Buried Drip Emitters are the preferred choice for arid regions with high evaporation rates or areas subject to freezing temperatures. Conversely, Wobblers (Sprinklers) are utilized when high dissolved oxygen levels are necessary and evaporation is not a critical constraint.

For gold and copper leaching, the limiting reagent is often Oxygen, rather than cyanide or acid. Sprinklers facilitate the aeration of the solution as it travels through the air. However, in cold climates like Canada or the Andes, spray systems freeze. The modern solution involves burying drip lines 30-50cm below the ore surface. This technique prevents freezing, eliminates evaporation (conserving water and heat), and prevents calcium scale buildup on the emitter tips. For sulfide ores requiring bacterial oxidation, low-pressure air injection piping installed at the bottom of the heap actively forces air into the pile, transforming it into an active aerated reactor.

Stability is prioritized over intensity in heap leaching operations. Effluent pH and flow rates are monitored hourly, as a sudden drop in pH often signals the presence of acid-consuming minerals that can halt recovery. To optimize operational costs and chemical efficiency, a strategy known as Pulse Leaching (Intermittent Irrigation) is recommended over continuous pumping.

Running pumps 24/7 is often chemically inefficient and energy-intensive. Implementing a cycle (e.g., spraying for 3 days, resting for 3 days) allows the heap to drain. During the “rest” period, fresh air (oxygen) is naturally drawn into the pore spaces of the rock. When spraying resumes, the fresh solution contacts this oxygenated ore, resulting in a spike in the dissolution rate. This method yields a higher grade pregnant solution (PLS) and significantly reduces pumping energy costs.

The appearance of “ponding” (pools of solution) on the heap surface indicates that Heap Permeability has been compromised. Increasing pump pressure in this scenario is counterproductive, as it further compacts the clogged material. The issue is typically caused by fines migration or chemical precipitation, such as gypsum or calcium carbonate.

The first remedial step is to cease irrigation in the affected zone to allow it to dry and crack, which naturally restores some air pathways. If the surface is sealed with a hard crust, shallow ripping with a specialized dozer (only on the top surface) is effective. For deep internal clogging, drilling vertical injection wells to bypass the blockage may be required. In cases of channeling, where liquid flows too rapidly through specific paths without contacting the ore, changing the chemistry (e.g., adding anti-scalant) or reducing the application rate to allow capillary action to wet the dry zones is necessary.

The mining industry is transitioning towards “Smart Heaps” and advanced thermal management. Operations are moving away from passive monitoring towards active visualization of the heap’s interior using electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) sensors. This technology allows for the real-time observation of moisture zones and dry spots.

Q1: What is the typical duration of a heap leach cycle?

The cycle duration depends heavily on mineralogy. Oxide gold ores typically require 60 to 90 days, while secondary copper sulfides may take 180 to 300 days. Utilizing active air injection can reduce these times by up to 30%.

Q2: Is it possible to heap leach ores with high clay content?

Yes, but it requires strict protocols. Aggressive agglomeration with high binder dosage is mandatory. Additionally, the lift height must be reduced (e.g., to 3-4 meters instead of 6 meters) to prevent the weight of the pile from causing self-compaction.

Q3: How does rainfall affect the heap leaching process?

Heavy rainfall can dilute the pregnant solution and cause water balance issues. In high-rainfall regions, storm water diversion channels and covered ponds are essential. The system must be designed to handle the “100-year storm event” to prevent environmental containment breaches.

Q4: What is the difference between Acid Leaching and Cyanide Leaching?

The choice depends on the target metal. Cyanide is used for gold and silver extraction in alkaline environments (pH > 10). Acid leaching (Sulfuric Acid) is used for copper, uranium, and nickel in acidic environments. The equipment materials must be selected to resist the specific chemical corrosion.

Q5: What are the requirements for Bio-leaching?

Bio-leaching requires a precise environment for bacteria (like A. ferrooxidans) to thrive. This includes maintaining specific pH levels, temperature (usually 30°C-45°C), and a constant supply of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Without air injection systems, bio-leaching is rarely effective in deep heaps.

ZONEDING Machine is a professional mineral processing equipment manufacturer established in 2004. The company provides comprehensive crushing, screening, and beneficiation solutions for mining operations globally. Technical teams specialize in optimizing the physical and chemical dynamics of processing plants to turn refractory ores into viable projects.

Ready to design a high-efficiency heap leach system? Contact ZONEDING for professional equipment selection and process configuration.

Unlock the economic and environmental benefits of tailings recycling. Discover how this sustainable solution transforms mining waste into valuable materials.

View detailsUnlock maximum gold recovery. Our guide details a high-yield, high-enrichment placer gold processing scheme, from screening to final concentration.

View detailsOptimize mineral processing! Compare spiral classifiers vs. hydrocyclones. Learn 5 differences to select ideal equipment for efficiency & beneficiation.

View detailsChoosing your fluorite processing equipment? Discover critical factors like ore characteristics, capacity needs, and cost-efficiency to select the best machine.

View detailsWe use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. If you continue to use this site we will assume that you are happy with it.

Privacy Policy